a garden report

on convivial tools, AI, Virginia Woolf, and beans

This weekend, I will tuck a dozen garlic cloves into the small bed along the fence line, rake a pile of leaves on top to rot, and call it a wrap on this year in the garden. Everywhere I have lived over the last decade – house or apartment, rented or owned – I have planted a garden. Some were small; some were enormous, more than I could handle. There were the spindly tomatoes from the shady South Greensboro Street duplex, the ludicrous half-acre of butternuts and candy roasters in Virginia, the rat-chewed collards in Park View, and the irrepressible roselles that long, hot summer in Lincolnton.

This year marks the longest I have lived in one house since I was seventeen, and therefore the longest I have worked one piece of earth. The garden is the entirety of the yard around our house, maybe 1000 square feet, though I’ve never bothered to measure it. Since we moved here in December 2021, there have been bumper crops of Cherokee purple tomatoes, greasy beans, glass gem corn, Lottie collards, Beauregard sweet potatoes, spiny okra, and oh lord, the weeds: purslane, dock by the dozens, and castaway seedlings from my neighbor’s redwood tree, currently aglow with fall light.

Then there are some plants I’ve never been able to make happy here – the Catawba rhododendron sits stunted, the same size as when I planted it three years ago; the dahlias always shrivel in the late summer droughts; any and every cabbage variety I’ve planted gets devoured by whiteflies (though not the kale, still can’t figure that out). Last summer, field sparrows flew away with most of the sorghum crop.

My neighbor to the right, a garrulous retiree fond of leaning over the fence to gossip, recently delivered a lovely compliment: “Your garden looks straight out of the Shire.”1 This weekend, my neighbor to the left, a high school teacher like myself, shook her head in performative disbelief as she asked again, always rhetorically, “How did you learn to do all this?”

Of course I’ll take the praise. Twelve years and six gardens later though, I know that the point of the garden – the reason why I spend hours each weekend mussing about the soil – is not really that it produces food or even beauty. Gardening is a way to practice living in a form of time that is spiraling, cycling, helicoidal – rot and fertility, shade and sun, rain and drought, light and darkness. When I am gardening, I am living in a version of time that circles more than it strings, that values the processes of consideration and care more than the linear output of maximum beans.

I pause, I think, I stare at the sun. Will the pimentos do well here, in this plot? And what of the lettuces, first planted, first forgotten? Every winter, I map the plots, thinking of last year, what worked and what didn’t. What plants gave to the soil here, and which took what? As soon as I solve the issue of the aphids on the sungolds, spider mites come after the eggplants. There are always new pests, problems, and questions. I often think of the garden not as a series of plots but as a map across the seasons and years. This is what gardening is: observing, planting, weeding, sweating, waiting, but above all, perhaps the right word is simply learning.

Like most people in the United States, I am thinking a lot about AI – less about its wonders and horrors though, and more about the degree to which I want to resist it. This isn’t a piece about how or why to oppose the onslaught of slop that even wise people around me insist (without any trace of irony nor passing head-nod to historicism) is “the future.” The Editors of N+1 have already made the argument for resistance for me:

“As we train our sights on what we oppose, let’s recall the costs of surrender. When we use generative AI, we consent to the appropriation of our intellectual property by data scrapers. We stuff the pockets of oligarchs with even more money. We abet the acceleration of a social media gyre that everyone admits is making life worse. We accept the further degradation of an already degraded educational system. We agree that we would rather deplete our natural resources than make our own art or think our own thoughts. We dig ourselves deeper into crises that have been made worse by technology, from the erosion of electoral democracy to the intensification of climate change… [and] we hand over our autonomy, at the very moment of emerging American fascism.”

I am most distraught about these tools when I witness how readily they impact (some of) my students’ willingness to discover new information for themselves. “Chat” will tell them why Frederick Douglass made such emphatic use of juxtaposition; no need to consider the moral perils of remaining neutral on the question of slavery or abolition, which is to say, the question of humanity. Britannica and JStor now offer AI assistants that prompt users toward pre-written research questions before users have had an opportunity to think up their own. I cannot help but wonder whether these companies really think my students are that stupid.

In trying to understand why I find these tools not only deeply arrogant but oddly obsequious, I have been trying to think of the tools I do find meaning in: a pen, a shovel, a garden rake. But what is the source of their meaning to me? These are not tools, I think, that necessarily require connection with others. But they are convivial, in that they allow users to maintain autonomy and creativity through their use. I’m not alone in feeling this way, particularly when it comes to the garden. At several points in Olivia Laing’s The Garden Against Time, she describes the pleasure and power of seemingly puttering about the garden, piddling about from plant to plant with her gardening tools:

“What I loved, aside from the work of making, was the self-forgetfulness of the labour, the immersion in a kind of trance of attention that was as unlike daily thinking as dream logic is to waking.”

This is also how it’s been for me – with gardening of course, but also with research and writing. You start with one question, and it leads to another; a new text emerges, and you wonder how the author would respond to your questions; later, you find out he did, but in dialogue with another writer, the one who keeps coming up no matter what you’re reading; you read her work, your mind expands; you try out writing her argument as your own, but the fit isn’t right; you try it this way, then that, then, one day, you find a way to write the line as a circle, which returns you back to the question that set you down this road in the first place. When the desire for discovery deepens, the labor of exposition dissolves. Hours are lost in the process, and in them, real meaning found. But thinking takes time, the singular good of which my students are in startling short supply.

Potentially I am biased toward the slow, inefficient work of making connections across a wide range of cultural artifacts and time periods. Since I was an eighteen-year-old American Studies major, I have been steeped in interdisciplinary practice, tracing a constellation of methodologies and theories across an overlapping set of unruly fields. The questions are often the same but the means by which you might answer them are always changing: What stars will you alight on? What axises and poles will you shift to uncover that which is unknown to you? Inside the web of inquiry, time can become pleasantly loose as patterns emerge across texts and decades, carrying you toward your answers – or so you hope.

This ability to make connections across a wide range of subjects is theoretically the promise of AI tools like NotebookLM or Gemini Gems, which circumscribe your inquiry only to the data you provide to it. Making connections is one thing (process); drawing conclusions (product) is another. And I find far more value – admittedly a feeling more than a fact – in the making of the constellation, than in the fact of having lined it out. This is probably why I am a happier essayist than I am a scholar.

Because I have found both pleasure and power in the meandering process of research and writing, i.e. thinking, I am wary of any tool that promises to shortcut discovery and short-circuit curiosity. And, so as not to make my students into straw men, I should say that some of them feel the same way. This week in our Environmental Writing Workshop, I asked students to define “wonder” after reading an excerpt of Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s World of Wonders. Wonder, one student wrote, is “an unanswerable question…the realization of all you do not know.” Pressed in discussion whether this is a desirable feeling, she answered: oh, totally. As if it were that easy!

“It is an exhausting process; to concentrate painfully upon the exact meaning of words; to judge what each admission involves; to follow intently, yet critically, the dwindling and changing of opinion as it hardens and intensifies into truth,” Virginia Woolf wrote in “On Not Knowing Greek,” her ode on the thrills and trials of translation, an essay one hundred years old this year. Woolf writes that by struggling to understand Greek, we might finally arrive not at any answers but at asking:

“Are pleasure and good the same? Can virtue be taught? Is virtue knowledge? The tired or feeble mind may easily lapse as the remorseless questioning proceeds; but no one, however weak, can fail, even if he does not learn more from Plato, to love knowledge better. For as the argument mounts from step to step, Protagoras yielding, Socrates pushing on, what matters is not so much the end we reach as our manner of reaching it. That all can feel — the indomitable honesty, the courage, the love of truth which draw Socrates and us in his wake to the summit where, if we too may stand for a moment, it is to enjoy the greatest felicity of which we are capable.”

I quote Woolf at length to arrive at this : lucidity and liberation are in the asking, not the answers. AI promises an escape from both and all, shackling us to a future where to catechize is not quite criminal, it’s just beside the point. Past is really past; the present a collapsed doldrum on our way to a predetermined future. No matter the sad heights of competence and efficiency these tools provide, I cannot see the benefits of swindling ourselves of the wonder of not knowing and asking anyway.

It’s become a joke in our house – though admittedly not a very good one – that every year, by the end of May, I proclaim the garden to be the best we’ve ever had. The angelica erupts in fireworks, the strawberries plump and gleam, and the peas flower and fruit, green then greener. You never did see a beet like my tender little beets.

Two weeks later, though, it’s the worst garden we’ve ever had. The summer heat arrives, the weeds gobble all, and the eggplants wither for no other reason than I forgot to water them. This year, I mixed up the bush beans and pole beans, the latter of which, without a trellis, lolled about the aisles like rangy rattlesnakes.

The joke is funny, I guess, because so fucking what. The point of the gardening is the learning, and the known falsity of the promise that next year, I will have the best garden I’ve ever had. There is so much I still don’t know about plants, so many problems with plots and irrigation and soil and shade, and still – the garden is superabundant, even sublime.

This year I grew a gallon of dried beans. Shucked and stored, those thousands of beans now sit in a glass jar on my kitchen shelf, and I stare at them while I cook. Each bean is a minute I have spent in the garden, digging, thinking, weeding, and planting. They add up to something, I think, but I don’t know what. “What is a gallon of beans worth?,” I asked Gemini. After equivocating on the relative value of canned pintos versus dried black beans, it arrived at a final answer: “Less than $10,” it told me.

✧ not an AI-screed ✧ in other writing news ✧

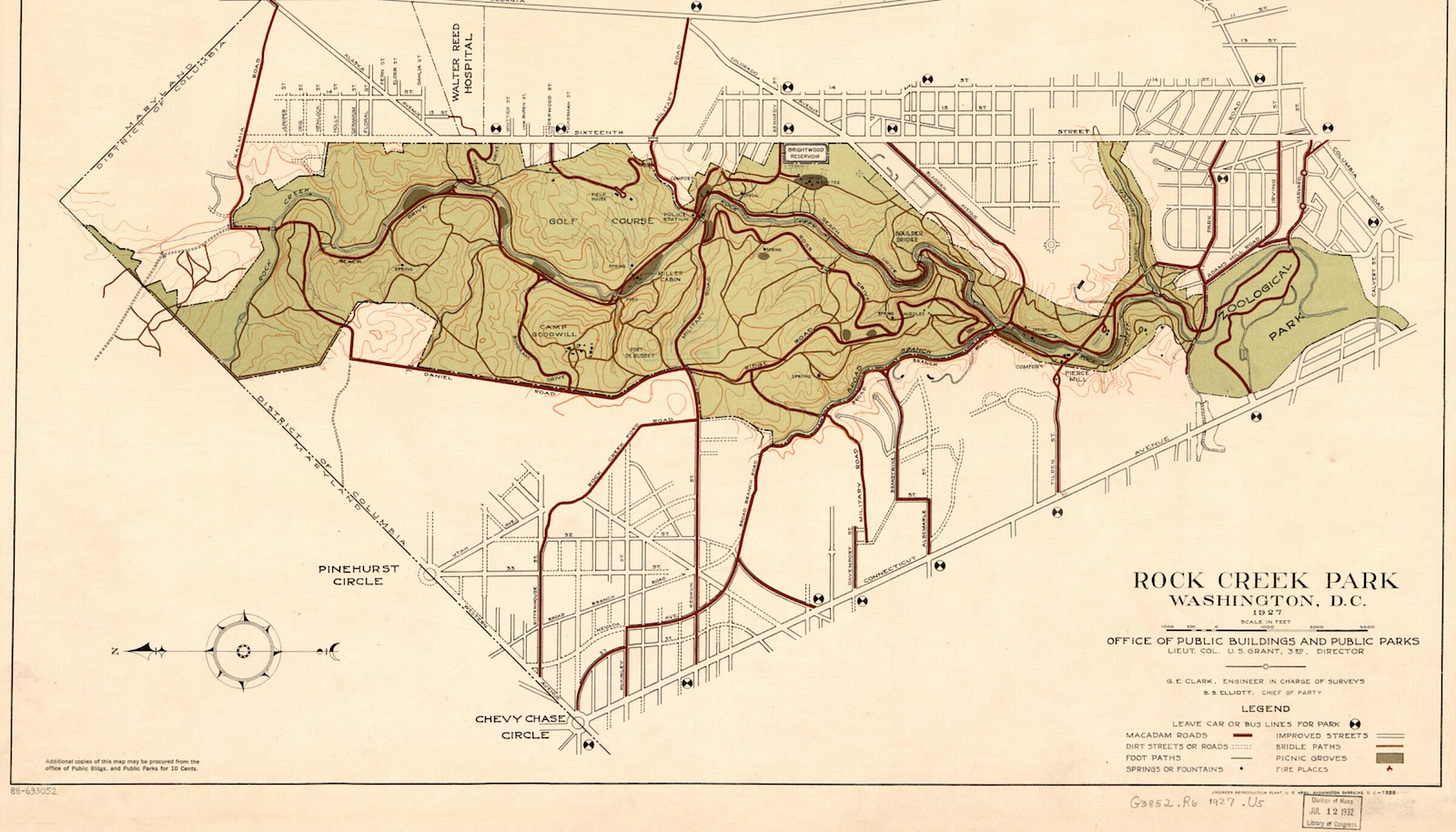

I am so glad that Orion gave me an opportunity to write about the Blackbyrds’ “Rock Creek Park,” and the ecology of Rock Creek Park in their Fall 2025 hip hop and ecology issue, guest edited by Hanif Abdurraqib. This is my first entree into music writing, and it’s surreal to be in the same issue as QUESTLOVE. Me and Questlove. We’re the same. We know the exact same amount about hip hop.

Also dope to see this piece featured in Longreads last week.

I have been having A TIME this month as the Inner Loop’s featured writer for November 2025. There are still TWO upcoming events that you can register for —

✧ On Monday, November 17th at 12pm, I’ll be talking with THE E. ETHELBERT MILLER about using historical research and environmental observation to read a landscape and reveal hidden histories within a specific place. You can register for that here. I mostly want to ask him to describe Washington, D.C. in 1975.

✧ And then I’m reading on Tuesday, November 18th at 7pm at Sonny’s Pizza in Park View — on the same block as the rat-chewed collards garden — with the Inner Loop. You can register for that too.

Thanks for subscribing, and reading to the end here. Hit that <3 button and share with a friend? Here’s the sunset looking upriver at Sycamore Island last week in thanks —

“The one small garden of a free gardener was all his need and due, not a garden swollen to a realm; his own hands to use, not the hands of others to command.” - J. R. R. Tolkien